Anyone who has played a tabletop roleplaying game has experienced that thrilling moment when excitement and utter terror crash together. That moment when all the planning and hard work comes together and there is a reckoning. When empires rise and kingdoms fall. I mean, of course, the time when you have to pick up the dice and roll them.

Dice are a simple device which can be modelled with probability (we all know the reality that dice are evil and vindictive, taking favourites and delighting in crushing dreams but that is a different post) and the results predicted with statistics. A skilled combat character (skilled by the numbers, ignoring the skill of the player) tends to do consistently well in combat situations, however if your experiences are anything like mine an equally skilled social or artistic character often a wildly varying rate of success - miraculous achievements and dismal failures appearing with alarming regularity. So why is there this difference? There are two main effects at play and brace yourself because there is going to be a little maths involved.

Firstly, there is the volume of dice rolls. The distribution of results from a die will tend towards the statistical prediction as the number of independent rolls increase. That is to say, if you roll a fair die once or twice you could get anything. If you roll it dozens of times you're likely to get a roughly equal number of each result. The more times you roll, the more even your results will be. To put it in more useful gaming terms, rolling lots of dice makes the outcome far more predictable.

In all RPG systems I have played, pretty much every action in a combat encounter requires some dice to be rolled. An entire social encounter (and especially a performance) is often modelled as a single roll. Couple this with combat usually taking the lion's share of the game time and you have vastly more combat dice being thrown than non-combat dice. The combat character gets the whole spectrum of results, with less riding on each individual roll so bad rolls can be countered with good. Eventually the character's skill pushes the average towards success. The non-combat character is at the mercy of the dice as they are usually stuck with their single roll, good or bad with the effect being amplified by the inherent variance in the system being played, which is to say that the outcome is far more based on luck.

Secondly, there are the mechanics available to player to give themselves an edge. In combat a character can fight defensively, move to higher ground, power attack, change stance and so on and used correctly all of these options change the rolls to sway things in their favour. The options available to the non-combat character are typically few and far between making it harder to take advantage of changing circumstances. This also makes the non-combat character less engaging as there are fewer choices to be made when using their primary skill.

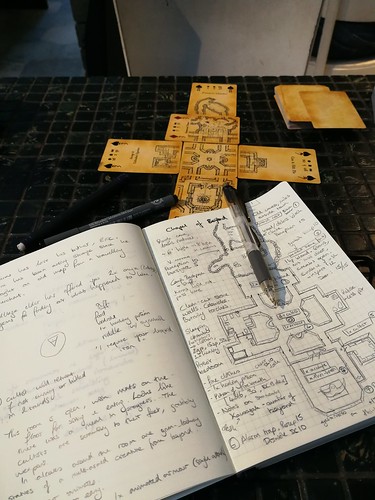

Both of these are a reflection of combat mechanics being more fully developed than social mechanics. If the game is combat-focused that doesn't matter too much, however my current game is focused on social encounters so I need a way to redress this balance.

A simple change is to have variable results depending on the dice. Missed the target number by five? Your performance was good but had mistakes. This works nicely when the non-combat encounters are not too important but unless the GM is very clear up front what will happen at different thresholds it is a bit vague and on its own it doesn't address inconsistency in the character's results or create more engaging mechanics to give the players more control.

I also want to avoided simply rolling more dice per minute. Although there is a lot to be learned from comparing the two, I think social encounters deserve to be treated differently to combat encounters. They are slower, with a longer burn-in time and more scope for laying foundations before the final, all-important action takes place. That means awarding bonuses for preparation - both in avoiding failure and enhancing success.

My first major concern is to find a way to avoid catastrophic failure from an experienced performer. A singer has a skill level which represents their ability to start singing on demand. If they are to perform at an important event they are unlikely to just wing it, instead practising to reduce the risk of failure. I'm modelling this by awarding static dice modifiers to players who spend time practising - essentially the end performance is easier because of the preparation. To get the desired effect, you really need to set the difficulty of the attempted performance at the beginning of the practice period as the aim is to make it more likely the character will succeed when the dice are rolled, not just move the same variance to higher numbers. A similar preparation for a social encounter might be to research the target's interests and pet peeves to avoid a faux pas.

I also want the players to be able to take actions to enhance their success - the equivalent of the combat modifiers. Pre-actions in a social situation would mean smaller activities which lead towards the intended goal. Trying to persuade a merchant to buy his products exclusively from your factory would be a hard check, but with the correct preparation it can become much easier. A character might do the merchant a series of favours first to create a strong relationship with them then conduct the negotiation in a relaxing environment whilst plying them with drink to slightly impair their judgement. An alternative approach would be to threaten the merchant then pay a contact to harass them over a period of days so they are distracted and sleep-deprived when the time comes to talk.

Both approaches have the character increasing their chance of success by taking minor actions in preparation which will give a numerical bonus in the final roll. The player is making decisions throughout as they are choosing their preparations and acting them out. The preparation also gives the opportunity to assess their opponent and the changing political battlefield. They might decide at any point that the final negotiation is a bad idea and try to pull out.

Allowing numerical advantages from preparation will not make many non-combat encounters significantly easier to overcome but I'm not going to increase the difficulty to compensate just yet. Game systems do not usually encourage preparation beyond perhaps setting a quick ambush so this is quite a shift in thinking and that will take time to embed but it should produce more engaging non-combat encounters driven by the players as well as giving them more control over the outcomes.